From The Seattle Times

By Dominic Gates

The pilots of the Ethiopian Airlines 737 MAX that crashed last month appear to have followed the emergency procedure laid out by both Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration — cutting off the suspect flight-control system — but could not regain control and avert the plunge that killed all 157 on board.

Press reports citing people briefed on the crash investigation’s preliminary findings said the pilots hit the system-cutoff switches as Boeing had instructed after October’s Lion Air MAX crash, but couldn’t get the plane’s nose back up. They then turned the system back on before the plane nose-dived into the ground.

While the new software fix Boeing has proposed will likely prevent this situation recurring, if the preliminary investigation confirms that the Ethiopian pilots did cut off the automatic flight-control system, this is still a nightmarish outcome for Boeing and the FAA.

It would suggest the emergency procedure laid out by Boeing and passed along by the FAA after the Lion Air crash is wholly inadequate and failed the Ethiopian flight crew.

A local expert, former Boeing flight-control engineer Peter Lemme, recently explained how the emergency procedure could fail disastrously. His scenario is backed up by extracts from a 1982 Boeing 737-200 Pilot Training Manual posted to an online pilot forum a month ago by an Australian pilot.

That old 737 pilot manual lays out a scenario where a much more elaborate pilot response is required than the one that Boeing outlined in November and has reiterated ever since. The explanation in that manual from nearly 40 years ago is no longer detailed in the current flight manual.

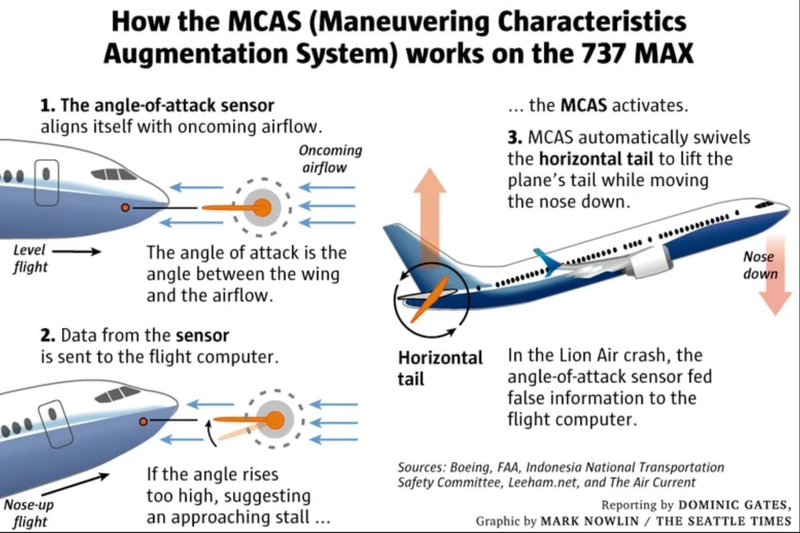

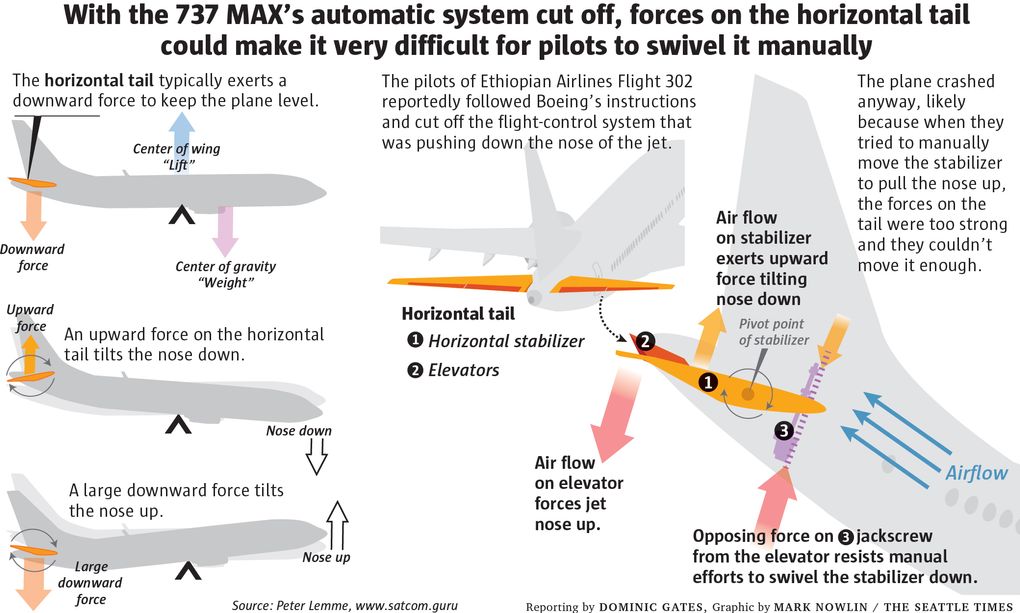

Just a week after the Oct. 29 Lion Air crash, Boeing sent out an urgent bulletin to all 737 MAX operators across the world, cautioning them that a sensor failure could cause a new MAX flight-control system to automatically swivel upward the horizontal tail — also called the stabilizer — and push the jet’s nose down.

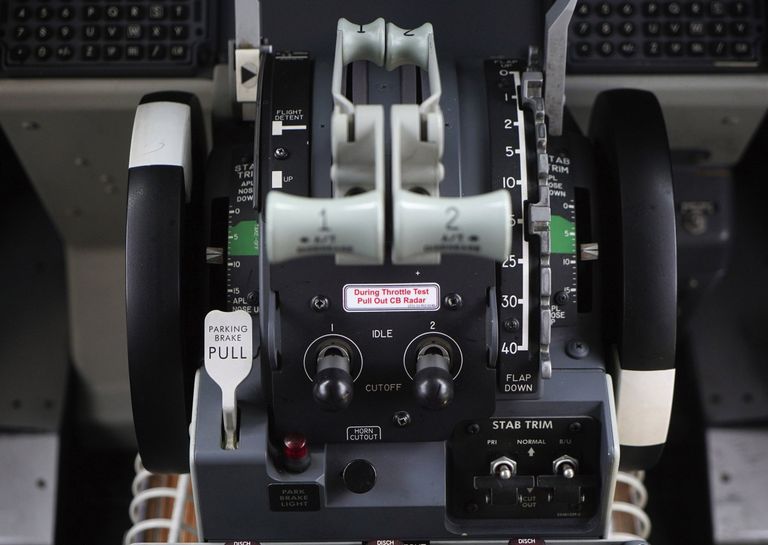

Boeing’s bulletin laid out a seemingly simple response: Hit a pair of cutoff switches to turn off the electrical motor that moves the stabilizer, disabling the automatic system — known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS. Then swivel the tail down manually by turning a large stabilizer trim wheel, next to the pilot’s seat, that connects mechanically to the tail via cables.

Boeing has publicly contended for five months that this simple procedure was all that was needed to save the airplane if MCAS was inadvertently activated.

In a November television interview on the Fox Business Network, Boeing Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg, when asked if information had been withheld from pilots, cited this procedure as “part of the training manual” and said Boeing’s bulletin to airlines “pointed to that existing flight procedure.”

Vice president Mike Sinnett repeatedly described the procedure as a “memory item,” meaning a routine that pilots may need to do quickly without consulting a manual and so must commit to memory.

But Lemme said the Ethiopian pilots most likely were unable to carry out that last instruction in the Boeing emergency procedure — because they simply couldn’t physically move that wheel against the heavy forces acting on the tail.

“The forces on the tail could have been too great,” Lemme said. “They couldn’t turn the manual trim wheel.”

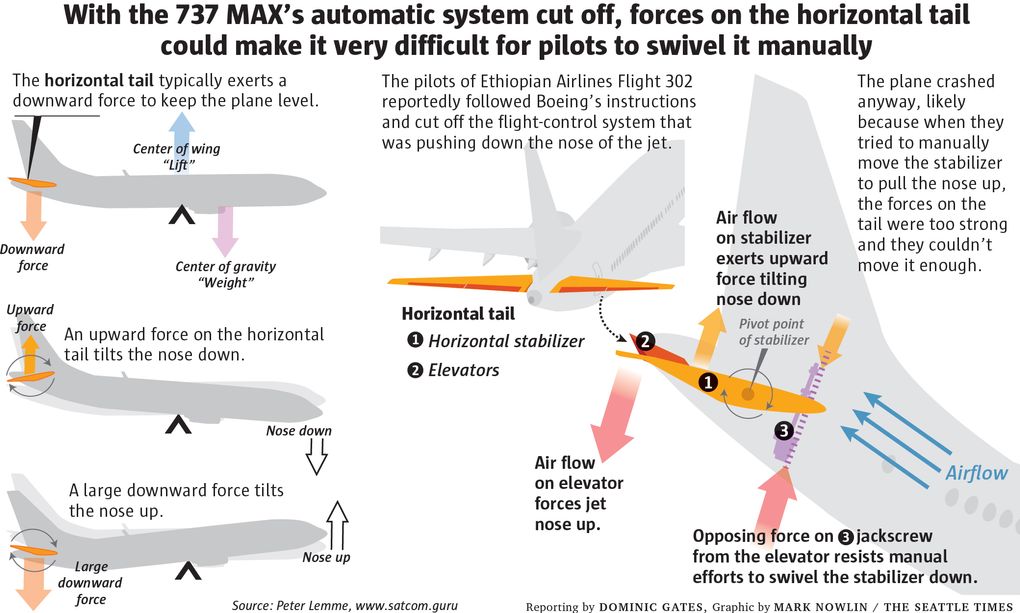

The stabilizer in the Ethiopian jet could have been in an extreme position with two separate forces acting on it:

- MCAS had swiveled the stabilizer upward by turning a large mechanical screw inside the tail called the jackscrew. This is pushing the jet’s nose down.

- But the pilot had pulled his control column far back in an attempt to counter, which would flip up a separate movable surface called the elevator on the trailing edge of the tail.

The elevator and stabilizer normally work together to minimize the loads on the jackscrew. But in certain conditions, the elevator and stabilizer loads combine to present high forces on the jackscrew and make it very difficult to turn manually.

As the jet’s airspeed increases — and with nose down it will accelerate — these forces grow even stronger.

In this scenario, the air flow pushing downward against the elevator would have created an equal and opposite load on the jackscrew, a force tending to hold the stabilizer in its upward displacement. This heavy force would resist the pilot’s manual effort to swivel the stabilizer back down.

This analysis suggests the stabilizer trim wheel at the Ethiopian captain’s right hand could have been difficult to budge. As a result, the pilots would have struggled to get the nose up and the plane to climb.

If after much physical exertion failed, the pilots gave up their manual strategy and switched the electric trim system back on — as indicated in the preliminary reports on the Ethiopian flight — MCAS would have begun pushing the nose down again.

Boeing on Wednesday issued a statement following the first account, published Tuesday night by The Wall Street Journal, that the Ethiopian pilots had followed the recommended procedures.

“We urge caution against speculating and drawing conclusions on the findings prior to the release of the flight data and the preliminary report,” Boeing said.

However, a separate analysis done by Bjorn Fehrm, a former jet-fighter pilot and an aeronautical engineer who is now an analyst with Leeham.net, replicates Lemme’s conclusion that excessive forces on the stabilizer trim wheel led the pilots to lose control.

Fehrm collaborated with a Swedish pilot for a major European airline to do a simulator test that recreated the possible conditions in the Ethiopian cockpit.

A chilling video of how that simulator test played out was posted to YouTube and showed exactly the scenario envisaged in the analysis, elevating it from plausible theory to demonstrated possibility.

The Swedish pilot is a 737 flight instructor and training captain who hosts a popular YouTube channel called Mentour Pilot, where he communicates the intricate details of flying an airliner. To protect his employment, his name and the name of his airline are not revealed, but he is very clearly an expert 737 pilot.

In the test, the two European pilots in the 737 simulator set up a situation reflecting what happens when the pre-software fix MCAS is activated: They moved the stabilizer to push the nose down. They set the indicators to show disagreement over the air speed and followed normal procedures to address that, which increases airspeed.

They then followed the instructions Boeing recommended and, as airspeed increases, the forces on the control column and on the stabilizer wheel become increasingly strong.

After just a few minutes, with the plane still nose down, the Swedish 737 training pilot is exerting all his might to hold the control column, locking his upper arms around it. Meanwhile, on his right, the first officer tries vainly to turn the stabilizer wheel, barely able to budge it by the end.

If this had been a real flight, these two very competent 737 pilots would have been all but lost.

The Swedish pilot says at the start of the video that he’s posting it both as a cautionary safety alert but also to undercut the narrative among some pilots, especially Americans, that the Indonesian and Ethiopian flight crews must have been incompetent and couldn’t “just fly the airplane.”

Early Wednesday, the Swedish pilot removed the video after a colleague advised that he do so, given that all the facts are not yet in from the ongoing investigation of the crash of Flight 302.

More detailed instructions that conceivably could have saved the Ethiopian plane are provided in the 1982 pilot manual for the old 737. As described in the extract posted by the Australian pilot, they require the pilot to do something counterintuitive: to let go of the control column for a brief moment.

As Lemme explains, this “will make the nose drop a bit,” but it will relax the force on the elevator and on the jackscrew, allowing the pilot to crank the stabilizer trim wheel. The instructions in the old manual say that the pilot should repeatedly do this: Release the control column and crank the stabilizer wheel, release and crank, release and crank, until the stabilizer is swiveled back to where it should be.

The 1982 manual refers to this as “the ‘roller coaster’ technique” to trim the airplane, which means to get it back on the required flight path with no force pushing it away from that path.

“If nose-up trim is required, raise the nose well above the horizon with elevator control. Then slowly relax the control column pressure and manually trim nose-up. Allow the nose to drop below the horizon while trimming (manually). Repeat this sequence until the airplane is trim,” the manual states.

The Australian pilot also posted an extract from Boeing’s “Airliner” magazine published in May 1961, describing a similar technique as applied to Boeing’s first jet, the 707.

Clearly this unusual circumstance of having to move the stabilizer manually while maintaining a high stick force on the control column demands significant piloting skill.

“We learned all about these maneuvers in the 1950-60s,” the pilot wrote on the online forum. “Yet, for some inexplicable reason, Boeing manuals have since deleted what was then — and still is — vital handling information for flight crews.”

Aviation safety consultant John Cox, chief executive of Safety Operating Systems and formerly the top safety official for the Air Line Pilots Association, said that’s because in the later 737 models that followed the -200, what was called a “runaway stabilizer” ceased to be a problem.

Cox said he was trained on the “roller coaster’ technique” back in the 1980s to deal with that possibility, but that “since the 737-300, the product got so reliable you didn’t have that failure,” said Cox.

However, he added, the introduction of MCAS in the 737 MAX creates a condition similar to a runaway stabilizer, so the potential for the manual stabilizer wheel to seize up at high airspeed has returned.

Cox said the failure of both Boeing and the FAA to warn pilots of this possibility will be “a big issue” as the Ethiopian crash is evaluated.

“I don’t think Boeing realized the complexity of the failure,” he said.

The procedure Boeing recommended to airlines after the Lion Air crash, which was repeated in an airworthiness directive issued by the FAA, includes a line near the bottom that “higher control forces may be needed to overcome any stabilizer nose-down” position. The instructions add that the pilots can use the electric system to neutralize the forces on the control column before hitting the cut-out switches.

But there’s no indication whatever in the wording that this is essential, and that heavy forces could render the manual stabilizer wheel almost immovable if the control column is not relaxed.

It’s possible the Ethiopian pilots, hyper alert after the Lion Air accident to the possibility that MCAS had activated, jumped straight to the end of the procedure checklist and hit the cut-off switches before attempting even to counter the nose-down movement with the thumb switches on the control column.

That would have subjected them almost immediately to the high tail forces that could have made recovery impossible.

The good news for Boeing is that the proposed software fix announced for MCAS should prevent the failure that led to this scenario in the cockpit.

“I think the MAX will be safe with the improved MCAS,” said Fehrm of Leeham.net.

On Wednesday, CEO Muilenburg joined Boeing test pilots aboard a 737 MAX 7 flight out of Boeing Field for a demonstration of the MCAS software fix and a test of various failure conditions. “The software update worked as designed,” Boeing said.

The bad news for Boeing is twofold, according to Fehrm. First, the original MCAS design was badly flawed and appears to be the principal cause of the Lion Air crash. Second, the procedure Boeing offered after that accident to keep planes safe now appears to have been woefully inadequate and may have doomed the Ethiopian Airlines jet.

On Wednesday the FAA , facing worldwide skepticism of its oversight, announced that it is establishing a team including foreign regulators to conduct a “comprehensive review of the certification of the automated flight control system on the Boeing 737 MAX aircraft.”

The Joint Authorities Technical Review, chaired by former NTSB Chairman Chris Hart and including experts from the FAA, NASA, and international aviation authorities, will evaluate all aspects of MCAS, including its design and pilots’ interaction with the system.

The preliminary investigation report into the Ethiopian crash is expected early Thursday and should offer definitive detail on what happened in the cockpit.